Wild Ginger is a perennial herb that grows within moist and shaded woodland settings with rich soil. Two main species of wild ginger are native to North America, the Asarum canadense and also the Asarum caudatum from the same genus. The A. caudatum species (commonly called western wild ginger) is found prolifically throughout the west of the US. Whereas A. canadense (often called Canada wild ginger) is found throughout the mid west (central regions) and eastern states, and large areas of southern Canada.

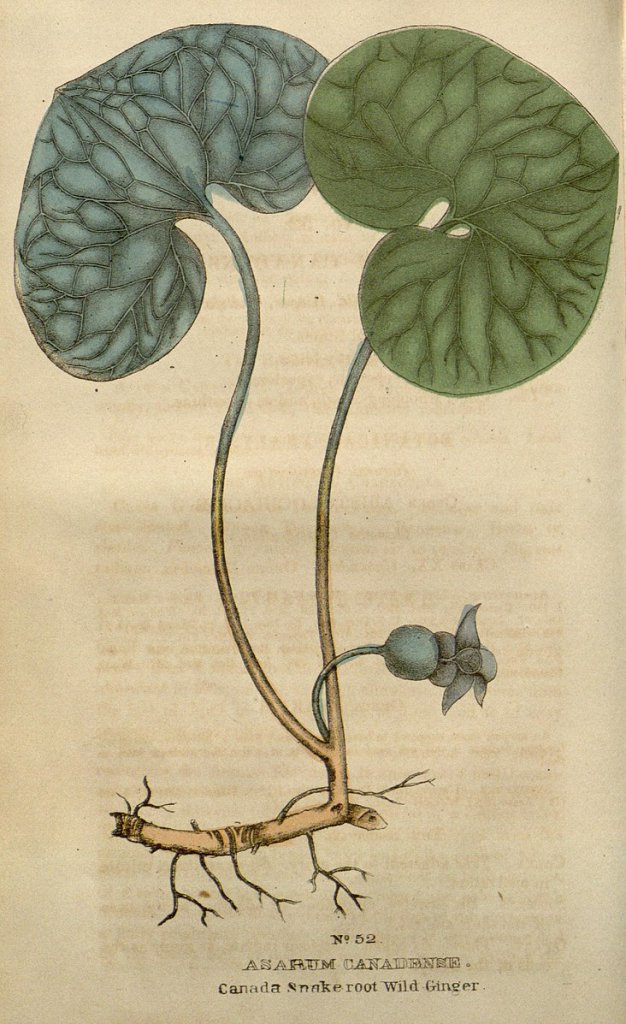

Wild ginger bears lightly crinkled, heart-shaped and matte green leaves. These leaves are approximately 3-7 inches wide and 10 inches in length. It is a particularly low growing plant, reaching no more than 12 inches from the ground. The flowers, which appear in late April, are very discreet, usually hiding beneath the carpet of leaves close to the soil. They have a deep brown/purple color, and 3 distinctive pointed sepals, with no petals. The stems and rhizomes from one plant spreads across the soil forming wide mats that mix with other ginger plants.

Edible parts and other uses

The stems, rhizomes and leaves of ginger all emit the aroma and taste of ginger. Albeit without the fiery heat cultivated ginger (Zingiber officinale) produces. Whilst the flavoring is pleasant and fragrant, wild ginger is not officially considered safe to consume due to toxins.

Some foragers claim the risk is only present if large amounts are eaten, however there are other ways to enjoy the flavor of wild ginger without risk. The toxins are not likely to transfer to water, so wild ginger tea and infusions should be perfectly safe to create. Once water has been steeped with wild ginger it can utilised in many ways, from cocktails to ice-cream!

Foraging

It tends to carpet wide areas of woodland floor, particularly along hiking or walking trails. So it is best to begin your search here. Wild ginger is a secure and fairly common species of woodland plant, so it shouldn’t be too long before you happen upon a patch.

The best time for unearthing the sweet and spicy rhizomes is early spring and late fall. This is because the plant is more likely to be dormant, therefore harvesting will be less likely to harm the plant. Essentially as long as the ground is not frozen you should be able to find the roots.

When collecting the rhizomes from just below the surface, be sure not to over harvest. This will ensure the plant is able to recover and regrow within the future. It is a relatively slow growing plant, so over harvesting could mean you can’t harvest from the same patch again for a number of years. Any additional rhizomes that you forage can be cleaned, dried and stored in an air tight container for use at a later date.

Cautions

Toxins known as carcinogens are present in wild ginger. These can cause damage to the kidneys or even develop into cancers if eaten in great quantities.

Whilst it may be safe to steep wild ginger in water, you should not infuse it with vinegars or alcohol as the toxins may still transfer.

Did you know…

Native Americans once used wild gingers in a variety of herbal remedies and medicines. From relieving digestive complaints, sore throats and urinary disorders. They would create liquid concoctions or poultices to soothe and heal.

Conclusion

Whilst out hiking or walking, keep an eye out for the cluster of tell-tale heart shaped leaves. Whilst the plants may not produce a huge yield of rhizomes or stems, you should be able to collect a good quantity for use in a pot of herbal tea and some extra for drying and storage.

—————Written by Hannah Sweet

Hannah is a freelance writer and graphic designer from the UK. With a penchant for travelling, photography and all things botanical, she enjoys writing about a wealth of topics and issues, from conservation and slow living, to design and travel. Learn more about her writing and design services at www.sweetmeanders.co

Many of our readers find that subscribing to Eat The Planet is the best way to make sure they don't miss any of our valuable information about wild edibles.

See our privacy policy for more information about ads on this site

One Response

Thanks. Ran out of grocery store ginger and was really tempted to use some of the wild ginger growing in our woodland property. Am super glad I asked Siri if it could be toxic. The info was fascinating and saved our health. Now that we’ve found you will have a good source for other goodies we have growing around here. Our 70+ bodies and family thank you.