The American chestnut tree (Castanea dentata) was once a common find within it’s range of habitat across the Northeastern states. Whilst exploring its native range, one in four trees that you would have found would have been an American chestnut. It has an extensive history, once being a tree of huge importance, it was frequently turned to for the resources it could provide. Sadly however, within the last century, its story took a tragic twist. Its population sizes have been largely decimated by a disease known as ‘chestnut blight’. First introduced into the US by chestnut species brought across from other continents.

The Arrival of the Blight

The Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima) and Japanese chestnut trees (Castanea crenata) were brought into the US in the late 19th century. Land owners and farmers hoped to cultivate and grow these species on a commercial scale. However a small number of these introduced species unfortunately brought with them the fungal disease ‘Chestnut Blight’ that caused the eventual demise of the American chestnut tree.

It is sadly now a critically endangered species and on the brink of extinction. Whilst the Chinese and Japanese varieties had built a stronger immune response to chestnut blight, the American species had no evolutionary attributes to help them fight the disease, meaning an infection was typically lethal. It spread like wildfire throughout woodlands and forest, and within a few decades the population had almost been wiped out. Research programmes are hoping to cross breed the American and Asian tree species, to produce a new variety that holds some resistance to the disease.

The non-native species of chestnut have now become strongly established within North American forests. Whilst the native American chestnut struggles to survive and compete. Chestnut species from China, Japan and Europe (Castanea sativa) (which also holds a slight resistance to chestnut blight) are now a much more common find than the American chestnut. A tree once so numerous, is now a rare find whilst out exploring.

Identifying Chestnut Trees

A number of American chestnut saplings can still be found in the wild. However, blight can linger in the soil and even remain dormant in oak trees. So often saplings are unable to mature and produce nuts. A small collection of mature trees still remain in random isolated pockets across the Northeastern states. So whilst populations sizes are low, you still have the opportunity to spot them.

Look out for their long, pointed, oval shaped leaves, with the tell tale serrated edges. The most distinguishing feature to look out for are the green spiny casings which hold the nuts. Although these will only be developing on the tree from late summer into early winter. The American chestnut is very similar to its non-native relatives, so it can be tricky to distinguish between them. However there are a few small characteristics which differ between species. For example, the American chestnut leaves tend to be broader and have more pronounced ‘toothed’ edges.

The Chestnut Tree as a Resource

Food

The fruits from the American chestnut were a coveted treat, particularly at Christmastime. Whilst chestnuts are still a popular winter treat, most commercially available chestnuts are likely to be the European species. After peeling chestnuts you can eat them raw, roasted or ground into flours and pastes for use in bread making and other dishes. Chestnut flour was once a cheap, plentiful and vital source of food for many impoverished people in Europe as well as the US.

However within the last few decades, as chestnut blight advanced, stocks of the tree were massively impacted. Whilst we depend less on the wild stocks of the nut today (and whilst the non-native chestnuts have replaced supplies in supermarkets etc.), many wildlife species were hugely affected by the loss of the American tree. A collection of wildlife dependent on the American chestnut are close to extinction, whilst others have already been lost. The American chestnut moth is now classified as extinct due its complete dependence on this native tree.

Medicine

Native Americans frequently used the American chestnut as a means to treat a number of conditions, from coughs and sores, and even in some instances, to stem bleeding. The nuts could be ground into powdered infusions, and even the bark and roots of the tree were utilised for their astringent properties.

Foraging

As a critically endangered tree, you can still forage for chestnuts, but great care must be taken to not damage or over harvest the tree. Make sure to leave nuts for wildlife, and most importantly as a means for the tree to produce new saplings. The best time of year to collect chestnuts is from the middle of September, until the end of November. Depending on your location, and the season, you might need to check back at different times to find the chestnuts when ripe.

It’s best to wait until the chestnuts fall to the ground, as climbing or shaking the tree could incur damage. Fully ripened chestnuts will have opened slightly, with the spiny burr revealing the nut within. Venture out in the early morning, particularly after a windy night and you’ll be able to collect a good number of freshly fallen chestnuts. Make sure to leave behind any with holes, as these have likely been ruined by chestnut weevils. Also remember to take a pair of thick gloves!

Cautions to Keep in Mind

A common misconception is mistaking sweet chestnuts for the toxic horse chestnut, with their green spiny casings bearing a similar appearance. It is important to note the horse chestnut is poisonous, however, identification should be straightforward for a novice forager. Firstly the spines on a sweet chestnut are much finer and numerous, whereas the horse chestnut tends to bear fewer spines that are shorter. Horse chestnuts are generally slightly larger and rounder, as well as the leaf structure of the tree being easily distinguishable too. The horse chestnut leaf consists of 5-7 smaller radial leaflets, which begin to narrow and broaden before forming a slightly rounded leaf end. Whereas the American chestnut has single, pointed, lance-shaped leaves.

History

The American chestnut was once a very significant supply of food, for humans and animals alike. As such an abundant crop, many farmers used the endless supply of nuts as a feed for livestock, and they were a readily available food supply for native Americans.

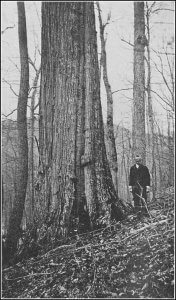

Due to their huge population sizes, they were a bountiful source of wood too. The trees grew quickly, reaching heights of 30m, and had a favourable grain patterning. This made them the wood of choice for furniture and structural components. The trees also contain high amounts of tannin, which would often be extracted for use in the tannin and leather trade of America. The American chestnut was a hugely valued tree, for all that it could provide.

Conclusion

Whilst the trees valued history is marred with the threat of a declining population, there is still positivity in their story. With small pockets of trees surviving, and the hope of disease resistance varieties, the future remains bright, not blight!

—————Written by Hannah Sweet

Hannah is a freelance writer and graphic designer from the UK. With a penchant for travelling, photography and all things botanical, she enjoys writing about a wealth of topics and issues, from conservation and slow living, to design and travel. Learn more about her writing and design services at www.sweetmeanders.co

Many of our readers find that subscribing to Eat The Planet is the best way to make sure they don't miss any of our valuable information about wild edibles.

See our privacy policy for more information about ads on this site

One Response

I am looking for sources of old Grove surviving and or semi resistant chestnuts trees. If anyone knows. Feel free to contact me….

Yetzertov7@yahoo.com

Jon makay