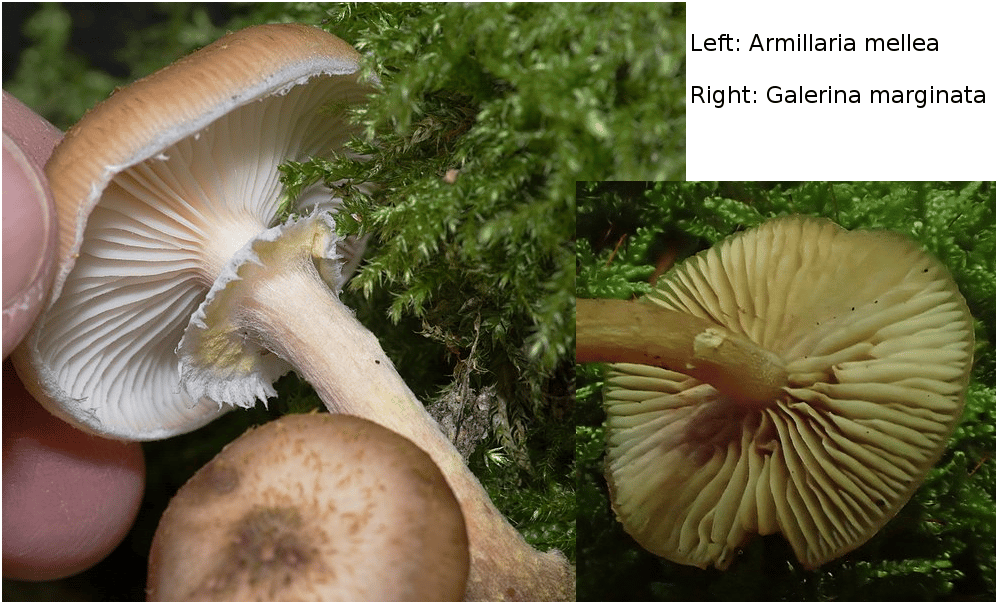

Note: Because Armillaria species are quite similar to some inedible “little brown mushrooms”, to include the highly toxic deadly galerina (Galerina marginata), and because they can sometimes cause some gastric upset in their own right, this mushroom is not suitable for beginning mushroom hunters, and should be collected and identified with caution.

The term honey mushroom refers to a collection of very similar species in the genus Armillaria. The one most frequently cited in foraging materials is A. mellea, though you may also find mention of others like A. ostoyae or A. gallica. All of them are rather small, honey-brown mushrooms with caps only a few inches across, and slender stipes.

A Headache for Foresters

If you look up honey mushrooms online, a lot of the information you’ll find is about how to control or avoid it. This is because some Armillaria are facultative saprophytes that cause white rot disease in living trees, though others only grow on dead wood. They are capable of breaking down and digesting both cellulose and lignin in wood, and because each species parasitizes different types of tree, there are very few that are not susceptible to at least one Armillaria species. It’s exceptionally difficult to eradicate once established in a grove of trees, which can lead to massive loss of timber.

A flush of honey mushrooms is not the only sign that Armillaria has infected a tree. These fungi produce rhizomorphs, root-like structures that can grow out from an existing colony’s mycelium in search of new hosts to infect. The rhizomorphs are often black due to native melanin content, and absorbing metals from the soil. This helps protect them from UV radiation. You may see rhizomorphs growing on or around an infected host tree.

Identifying and Preparing Honey Mushrooms

Because Armillaria spp. are among a number of small, nondescript brown mushrooms (also known as “LBMs” for “little brown mushrooms”) they can be difficult to differentiate from inedible or toxic lookalikes. Most honey mushroom caps are less than three inches across, though a few species may reach five inches in diameter. The cap color is honey to reddish brown; the center is usually darker, and the outer edge often has striations, or small vertical lines, all around it.

The stipe tends to be quite slender, is light at top and darkens toward the base, and usually has a distinctive ring or annulus around it a little below the cap. (The edible ringless honey mushroom, Desarmillaria caespitosa, is no longer considered to be in the genus Armillaria and this article does not apply to it.) If you split the stipe open it has a fibrous white pith in the center, something its lookalikes lack. It has true gills that are all straight and tightly packed. The gills are pale when young, but may darken with age depending on species.

Honey mushrooms grow in clusters on rotting wood and usually fruit in fall. While there are other LBMs that grow on wood, honey mushrooms have white spores whereas the others tend to have darker spores. A cluster of honey mushrooms will all grow from the same spot, whereas some lookalikes may grow from multiple, closely spaced bases. Also, the other species lack the ring/annulus, and do not have the fibrous core in their stipes.

Some mushroom hunters will discard the stipes as they can be tough due to the fibrous pith. However, they can still be made into mushroom broth; the pith can also be sauteed or otherwise cooked. The caps are more versatile and can be sauteed, added to soup, eggs and other dishes, or used in mushroom-based dressings and fillings. It is VERY important to thoroughly cook honey mushrooms before consuming them, as undercooked ones can cause gastrointestinal distress. Some sources recommend parboiling them before cooking them again in other recipes.

Avoiding Dangerous Lookalikes

As mentioned above, honey mushrooms are the only LBMs growing on single bases on rotting wood, with a ring/annulus on the stipe of each mushroom, white spores, and the fibrous core at the center of the stipe. By far the most dangerous lookalike is the deadly galerina. If you look under this toxic mushroom’s gills you’ll notice they’re more widely spaced and some of them may be wavy in appearance; they’re often a little darker in color. The spores are brown rather than white, and the stipe lacks the core.

Some inedible Pholiota species also look similar to honey mushrooms. However, they also have brown spore prints rather than white, and their caps often have a scaly appearance. Sulfur tufts (Hypholoma fasciculare), which can make you quite sick, has a bitter taste even when cooked, and has a dark brown spore print.

Clearly, if you’re going to attempt to identify honey mushrooms, the spore print is a crucial part of getting an accurate identification. If it doesn’t have white spores, discard it.

—————

Written by Rebecca Lexa

Rebecca Lexa is a certified Master Naturalist in the Pacific Northwest. She teaches classes on foraging and other natural history topics, both online and off. More about her work can be found at http://www.rebeccalexa.com.

Many of our readers find that subscribing to Eat The Planet is the best way to make sure they don't miss any of our valuable information about wild edibles.

See our privacy policy for more information about ads on this site

One Response

liketoolookinthewoodsfordifferent