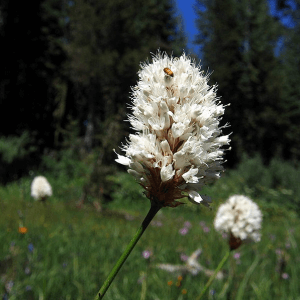

Western Bistort (Polygonum bistortoides) is a common wildflower that can be found in Alpine, Subalpine, and Meadow habitats throughout the Pacific Northwest. It also goes by Snakeweed colloquially because of the way the darkened root folds upon itself like a snake. It is in flower from June to September, and the seeds ripen from August to October. The species is hermaphrodite (has both male and female organs) and is pollinated by Insects.

This plant is native to the Pacific Northwest. As such, it was a staple food for Native American peoples. Medicinally, it was used as a poultice, ground into a fine powder, and applied damp to blisters, cuts, sprains, and abrasions. Sore throats, sore and bleeding gums, and boils were all treated by mixing the powdered root with water. The taste has been described as reminiscent of chestnut.

Non-Native American uses have been documented as well. The Botanist John Hill wrote in 1740 that Bistort is one of “the strongest astringent medicines in the vegetable kingdom and highly styptic and may be used to advantage for all bleedings, whether external or internal and wherever astringency is required.”

The plant has many edible parts. The young leaves before the plant flowers are the most palatable. They go well mixed into heavy soups and stews. The young leaves can also be used in place of raw greens such as spinach. Roots on this plant are substantial and the most commonly gathered part of the plant. Roots can be dried and ground into flour or put into soups for flavoring agents. You can also fry the roots in butter for a simple meal. Seeds are also edible. Any other root herb could be used if you do not have this plant handy. It is a simple carbohydrate.

To prepare the roots for consumption, scrape the outer bark to expose the white root. Pink roots will have a bitter taste. You should know that cooking is not required but recommended for optimal flavor. Vitamin A in the raw leaves. Roots are a source of starch and tannins (boiling the root reduces the tannins).

A word of caution about this plant taken directly from the Plants for a Future page, “Although no specific mention has been made for this species, there have been reports that some members of this genus can cause photosensitivity in susceptible people. Many species also contain oxalic acid (the distinctive lemony flavor of sorrel) – whilst not toxic this substance can bind up other minerals making them unavailable to the body and leading to a mineral deficiency. Having said that, a number of common foods such as sorrel and rhubarb contain oxalic acid and the leaves of most members of this genus are nutritious and beneficial to eat in moderate quantities. Cooking the leaves will reduce their content of oxalic acid. People with a tendency to rheumatism, arthritis, gout, kidney stones or hyperacidity should take special caution if including this plant in their diet since it can aggravate their condition.”

In conclusion, were you to find yourself on a brisk mountaintop walk in the PNW and look down, you may find yourself in a lovely field of Bistort. You can now walk firmly in the knowledge that this native plant was utilized by those who came before. You might eat a raw leaf, take the roots home, and boil them yourself. Getting to know the plants of the area is half the fun.

—————

Written by Shauna Wildey

She is a mother of three turned writer living along the Third Coast in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She is a trained herbalist at the Naturopathic Institute of Therapies and Education in Mt Pleasant, Michigan. She is a certified reiki master and yoga instructor, a metalsmith, and carries a BA in History. Inquiries can be sent to shaunamarie87@gmail.com

See our privacy policy for more information about ads on this site

Many of our readers find that subscribing to Eat The Planet is the best way to make sure they don't miss any of our valuable information about wild edibles.