For decades many people’s response to a pounding headache has been to take a couple of aspirin with some water. What most don’t realize is that this reliable medicine is derived from salicylic acid (or salicin), a compound found in many plants such as myrtle, poplar, and willow trees. Although many modern pharmaceutical drugs are rooted in the natural world, the aspirin-willow connection is probably one of the best known even among non-herbalists. But how much truth is there to the lore?

What is a Willow?

Willows are members of the genus Salix, which contains about four hundred species, found throughout temperate areas in the Northern Hemisphere. These trees and shrubs are all deciduous, and are frequently found in riparian zones or other damp locations. They may be pioneer plants in disturbed areas where conditions are favorable to them, and since they may start growing leaves as early as February in some areas, they can often make the most of the returning sunlight long before other plants. This makes them quite competitive in their ecosystems, and it is not uncommon for Salix species to be among the most dominant shrubs or trees found there. Unlike most plants, willows actually become more diverse the further north you go, and in some northern ecosystems they are among the most crucial species in their ecosystems.

Most willows have long, slender leaves, though some are rounder. They frequently have serrated edges. Most species will lose their leaves in fall, often after other deciduous trees have shed theirs. Many species will readily hybridize with other Salix in the area, which can lead to some confusion in identification as the hybrids combine traits of both parents. Moreover, some willow species are so similar that often only small details, such as flower shapes, can be used to reliably distinguish them from each other.

Notable Willow Species

There are too many species to list here, but there are a few in particular worth mentioning. Perhaps the best-known specimen, particularly in the horticulture industry, is the weeping willow (Salix babylonia). This tall, stately tree is known for its incredibly long, sweeping branches that can reach all the way to the ground. While it is native to China, it has been cultivated in other areas of Asia for thousands of years, and was traded along the Silk Road to Europe. It has since been introduced to dozens of countries around the world as an ornamental tree.

Europe and western to central Asia are home to several other common willow species. The goat willow (Salix caprea) is distinguished by its particularly large, round leaves; it is very closely related to the native American pussy willow (Salix discolor.) The eastern crack willow (Salix euxina) is native to areas around the Black Sea, but has been introduced to several other areas in Europe. It can be readily crossed with the white willow; the resulting hybrid, Salix x fragilis, is so hardy it actually outcompetes its euxina parent.

North America also has quite a suite of willow species in addition to S. discolor. The gray willow (Salix glauca) grows in large portions of Canada and the western United States, as well as Greenland, Siberia, and parts of Europe. Black willow (Salix nigra) grows in the eastern United States and Canada, while coyote willow (Salix exigua) occupies all but the northernmost parts of North America, and is also absent from the southeast. Perhaps the smallest of the genus, the dwarf willow (Salix herbacea) creeps along the ground, rarely getting more than two and a half inches high; it can be found not only in the Appalachians and eastern Canada, but also Greenland, the Alps and Pyrenees mountains, and Arctic portions of northwest Asia.

The White Willow

White willow often lives fast and dies young, as it is vulnerable to several diseases and parasites. Aphids are quite common, as are lace bugs, gall mites, and several species of caterpillar. Diseases that can strike white willows include watermark disease, willow heart rot, blight, silver leaf, honey fungus (Armillaria) and rust, among others. This susceptibility makes them less popular for timber, though the wood may be used for baskets, archery bows, and other tools, and particular hybrids may be grown for cricket bats.

The white willow is the best-known species associated with medicinal uses, particularly its connection to aspirin. But a little deeper digging throws this legend into question.

Willow Tea: The Original Aspirin?

By the 17th and 18th centuries, willow had fallen out of favor in the writings of both formal physicians and household formulae in western Europe, particularly England. By the time John Quincy wrote his Pharmacoepia Officinalis, he stated that no one actually took willow seriously as a medicine any more. This was at a time when western European physicians were relying more heavily on imported plants from elsewhere in the world, so it may be that native plants were disregarded simply for being too familiar, and physicians increasingly ignored the oral traditions passed down through families. Even in the early years of the 20th century, after aspirin was a well-known medicine, horticulturist and herbalist Maud Grieve suggested willow be used for a variety of medical purposes, but not to relieve pain or fever.

However, some indigenous American cultures have used the bark of S. discolor, and likely other species, as a painkiller and fever reducer in traditional medicine for millennia. And medical records dating from 3500 years ago in Egypt also discussed the use of willow for general pain relief. So the skepticism may be a case of Eurocentric thinking coupled with professionals distancing themselves from lay knowledge.

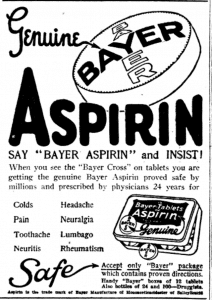

It wasn’t until 1757 when Rev. Edward Stone began using willow bark to treat a fever that the road to modern aspirin began; its bitterness led him to wonder whether, like the similar-tasting cinchona (quinine), it could be used medicinally. He reported his experience to the Royal Society; later 19th century chemists, like Henri Leroux and Raffaele Piria, spent decades further isolating and refining salicin. In 1899 the company that would become Bayer filed a patent for the name aspirin for their modified, concentrated version of the chemical.

That being said, those who wish to make use of willow’s combination of chemical compounds for medicinal purposes still have options today, whether gathering plant materials from the wild, or growing their own plants.

A Garden of Willows

If you’d like to grow willow trees in your yard, you’re in luck! They’re incredibly easy to cultivate from cuttings any time of year, though spring is best. All you have to do is obtain cuttings that are about ten to twelve inches long from the host tree, then place them with the cut ends in water. Once roots form you can plant them in soil, and make sure it stays damp at all times. Be aware that willow roots can travel quite a distance from the tree, so don’t plant them anywhere near houses or driveways.

Willows are so darn good at reproducing this way that you can actually make a rooting formula from them for use on other plants! Get a bunch of slender green willow twigs and remove the leaves. Then cut the twigs into pieces one inch long or less. Put them in boiling water, and let them sit for one to two days. This allows a type of hormone known as auxin to seep out of the twigs and into the water; as the base word aux-, which means “to support” suggests, this hormone is a key promoter of root growth in plants. Strain the water to remove the twigs, and then use it right away. If you need to store it, it will keep up to a couple of months in a closed container in the fridge, but its potency is best when fresh.

—————

Written by Rebecca Lexa

Rebecca Lexa is a certified Master Naturalist in the Pacific Northwest. She teaches classes on foraging and other natural history topics, both online and off. More about her work can be found at http://www.rebeccalexa.com.

Many of our readers find that subscribing to Eat The Planet is the best way to make sure they don't miss any of our valuable information about wild edibles.

See our privacy policy for more information about ads on this site